My lesson observation + coaching template

I take this into every lesson I watch, and use this in every coaching session I deliver

***Do you fancy winning £200 to spend on classroom equipment of your choice? One early winner has used the money for mini-whiteboards, protractors and purple pens! Just assign our brand new Baseline quiz to your students and you are in with a chance! You will also learn more about your students’ understanding than ever before. Visit here for more details.***

I have been doing some version of coaching teachers for over 15 years. The problem is, I was pretty rubbish at it for many of those years. I would observe a colleague teach, make vague notes, and then give meaningless, unactionable feedback like you need to work on your pace.

Terrible.

Over the last 18 months, I have tried hard to get better at observing lessons and delivering the subsequent coaching sessions. Any improvements I have made have been down to three people:

Adam Boxer - in particular, his Hypothesis model

Ollie Lovell - our monthly podcast conversations regularly include coaching reflections, for example, this one and this one

Josh Goodrich - his fantastic Responsive Coaching book, and our podcast conversation about it

Using lessons from these three greats, I have put together a template I use in each lesson I observe and each coaching session I deliver. In this post, I will walk you through it, describing the purpose of each section and illustrating it with a concrete example from a recent lesson and coaching session.

High-level overview

Here are the seven sections of my template:

Context

Lesson commentary

Specific praise to prompt

Hypothesis

Critical evidence

Diagnostic questions

Suggested action

At the top of my template, I have the following image of the 6 fundamental problems of teaching from Josh Goodrich’s Responsive Coaching book, as they help me identify specific praise and form my hypothesis.

Here is a Google Doc version of my template to download in case it is useful.

The technology

I have this template on an Evernote doc. I am a big fan of Evernote as it allows me to easily import photos into the template (as we will see, photos play a big part in my observation and coaching process), and I find the search function powerful.

But this template could just as easily be used on any note-taking app, or simply using pen and paper.

I also use the voice recorder on my phone to capture audio from the lesson.

Finally, I offer the teachers I work with the opportunity to have their lesson videoed. In this case, I use the camera on my iPhone, mounted on a tripod at the back of the lesson, with a Bluetooth clip-on mic attached to the teacher.

1. Context

I write anything I have been told in advance that may be relevant to the lesson or the teacher taking part in the coaching. Examples include:

Where in the curriculum this current lesson sits

The set / prior achievement level of the class

How experienced the teacher is

Any specific area of their practice or the lesson they want me to pay particular attention to

Example

I observed a teacher with 8 years of experience, teaching a middle-set Year 9 class about simple interest. This was the second in a series of lessons on maths and money. The teacher had not asked me to look a anything in particular. I observed the first 30 minutes of the lesson.

2. Lesson commentrary

As soon as I enter the room, I take a photo of the teacher’s board. I find photos useful when reflecting on the lesson, and they are also powerful to use as a frame of reference or catalyst for discussion in the specific praise and diagnosis part of the coaching session. I will continue to take photos of the board throughout the lesson.

For the same reasons, if a teacher is about to begin an explanation, give some instructions, or orchestrate some questions and responses, I will often hit record on my phone’s audio recorder.

I also keep a brief timeline of the teacher's and students' activities. Again, this is useful for me when reflecting on the lesson and can also provide objective critical evidence in the coaching session.

Example

11:15 – first bell rings, Do Now on the board

11:22 – all students in the room, door closed

11:27 – teacher begins going through the Do Now

“Everyone I saw remembered that anything to the power of 0 is 1”

11:36 – teacher finishes going through the Do Now

…

3. Specific praise to prompt

Throughout the lesson, I look for specific things the teacher is doing well. Specific is the key here. So, I don’t write down things like: I liked your questioning. Instead, it is: I liked the question you asked Isaac about the first step when factorising a quadratic. The more specific, the more meaningful, and if supported by evidence such as a photo or a quote, even better. I aim to find around three specific things to praise the teacher for, and never more than five because the effect of each is diluted. Josh’s diagram at the top of my template helps here, giving a hierarchical checklist I can use.

I begin the coaching session by thanking the teacher for letting me observe their lesson, and then asking them to tell me some of the good things they did. This gets the coaching conversation off to a positive start, and also gives me an indication of how aware they are of the strength of their practice.

Until recently, I would then share my specific praise with them. Following advice from Josh Goodrich and Ollie Lovell, I now prompt that praise. So, I describe the action they did that I liked - such as the question to Isaac about factorising quadratics - but then ask them to tell me why they did it. This serves two purposes: It gives me better insight into how aware they are of their strengths and what effective teaching looks like, and it makes the praise more potent if they can identify it themselves.

Example

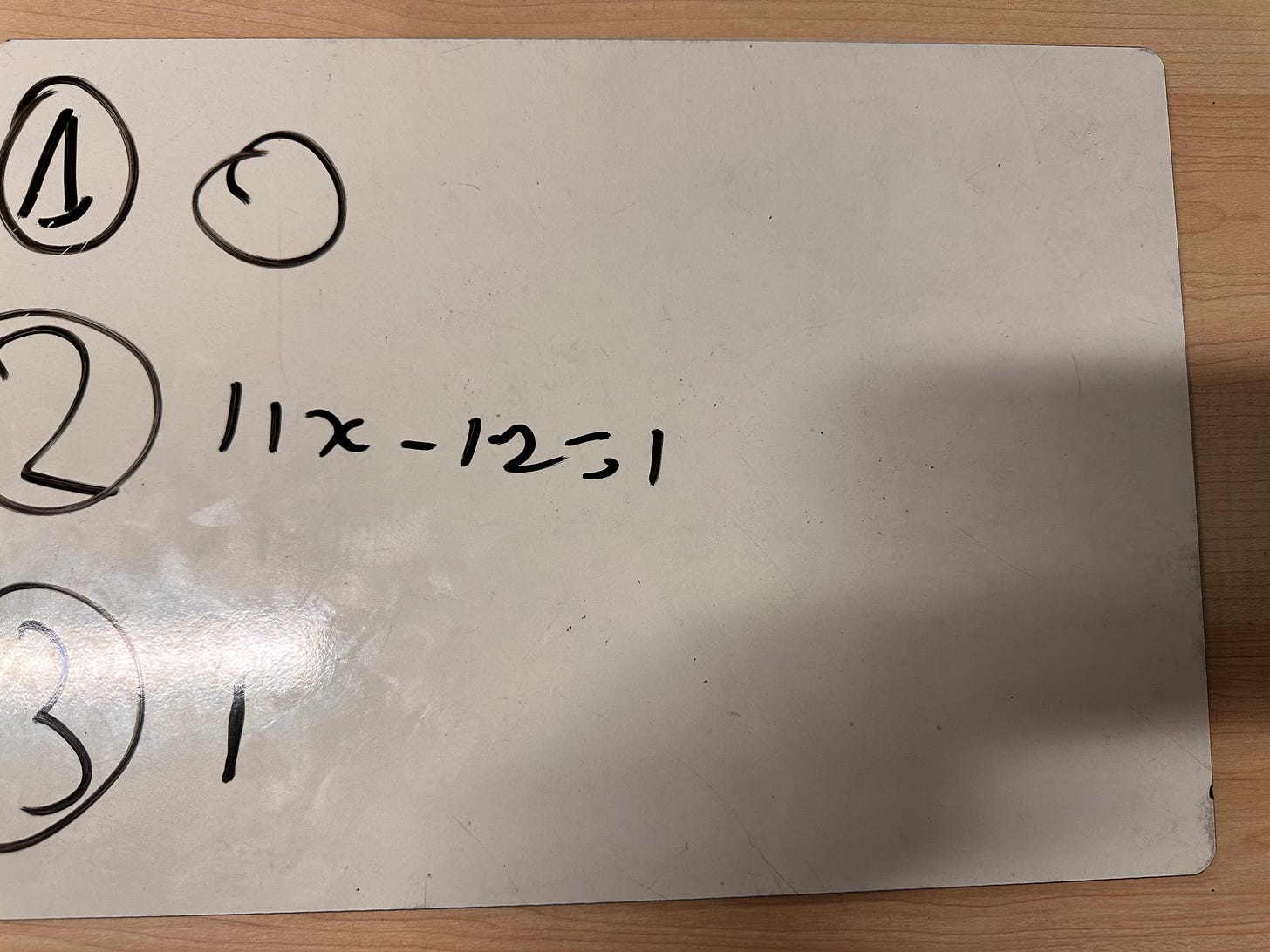

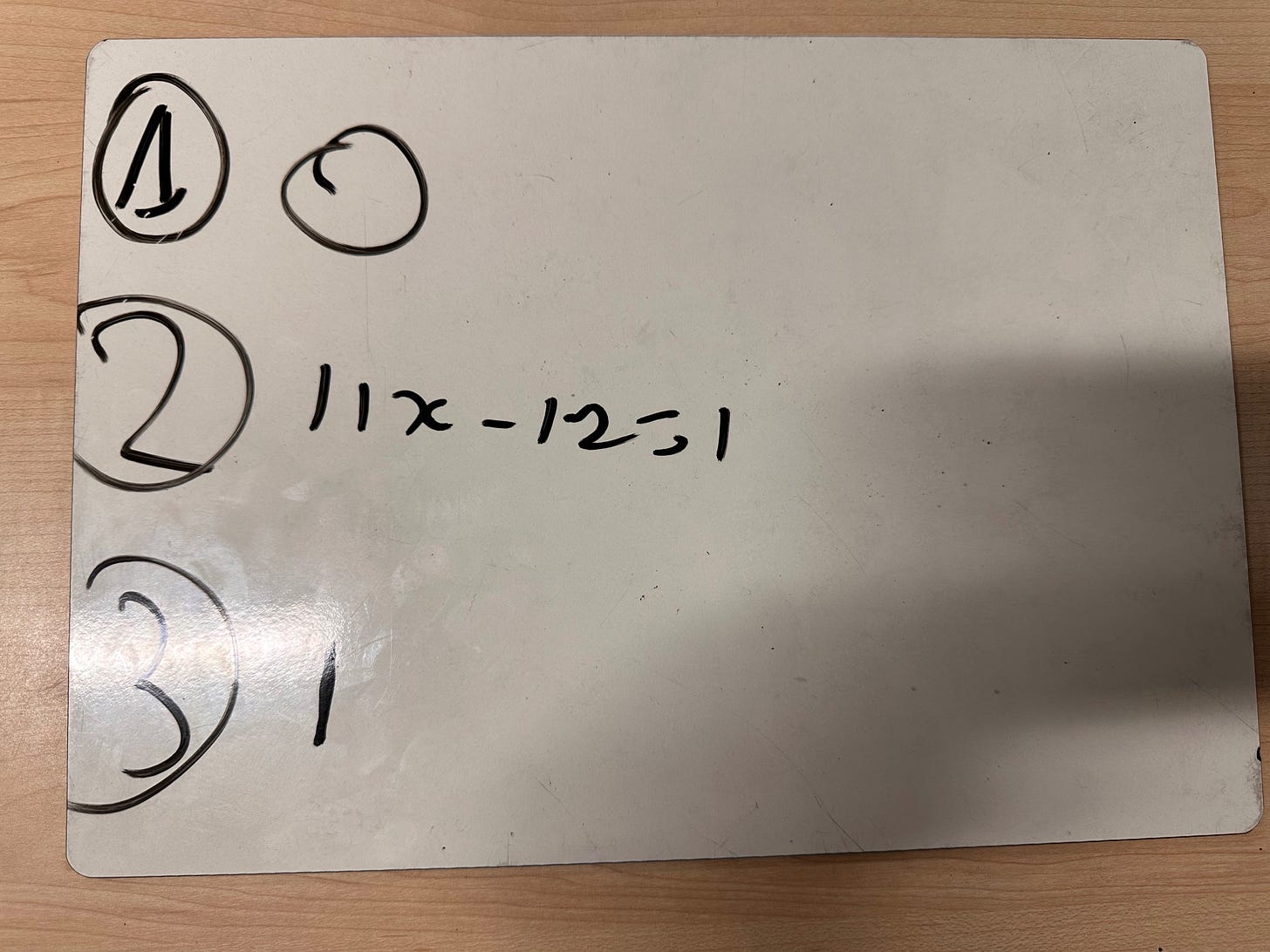

The use of mini-whiteboards throughout the Do Now was impressive as it enabled the teacher to check the understanding and effort of every student instead of hearing from just one or two.

There was a lovely moment when the teacher gave an explanation and then checked whether a boy at the back of the class had been listening (he hadn’t). The teacher reinforced the importance of listening, asked another student, returned to the boy and got him to repeat what they said, and then (this was my favourite bit) returned to the boy a few minutes later to check if he was still listening (he was).

The questions I asked the teacher were:

Tell me why you used mini-whiteboards in the Do Now

Talk me through the exchange you had with Reece

4. Hypothesis

This is the fun bit. I try to spot something in the lesson that isn’t going as well as it could be, or as well as the teacher thinks it is. As with the praise section, I find Josh’s diagram on the 6 fundamental problems of teaching beneficial here as it gives me an ordered checklist to work through:

Is the lesson pitched correctly? Yes.

Does the teacher have the students’ attention? I’m not sure…

Then, I need to form a testable hypothesis. Examples from recent lessons include:

Because you have not checked for listening, some students have not heard your explanation

Because of your choice of example, some students will be unable to answer this question

Because you have not addressed the fact that Sophie called out an answer, Sophie will call out another answer soon

Because you have not moved on when student responses indicate their understanding is secure, your Do Now will take longer than the planned 10 minutes

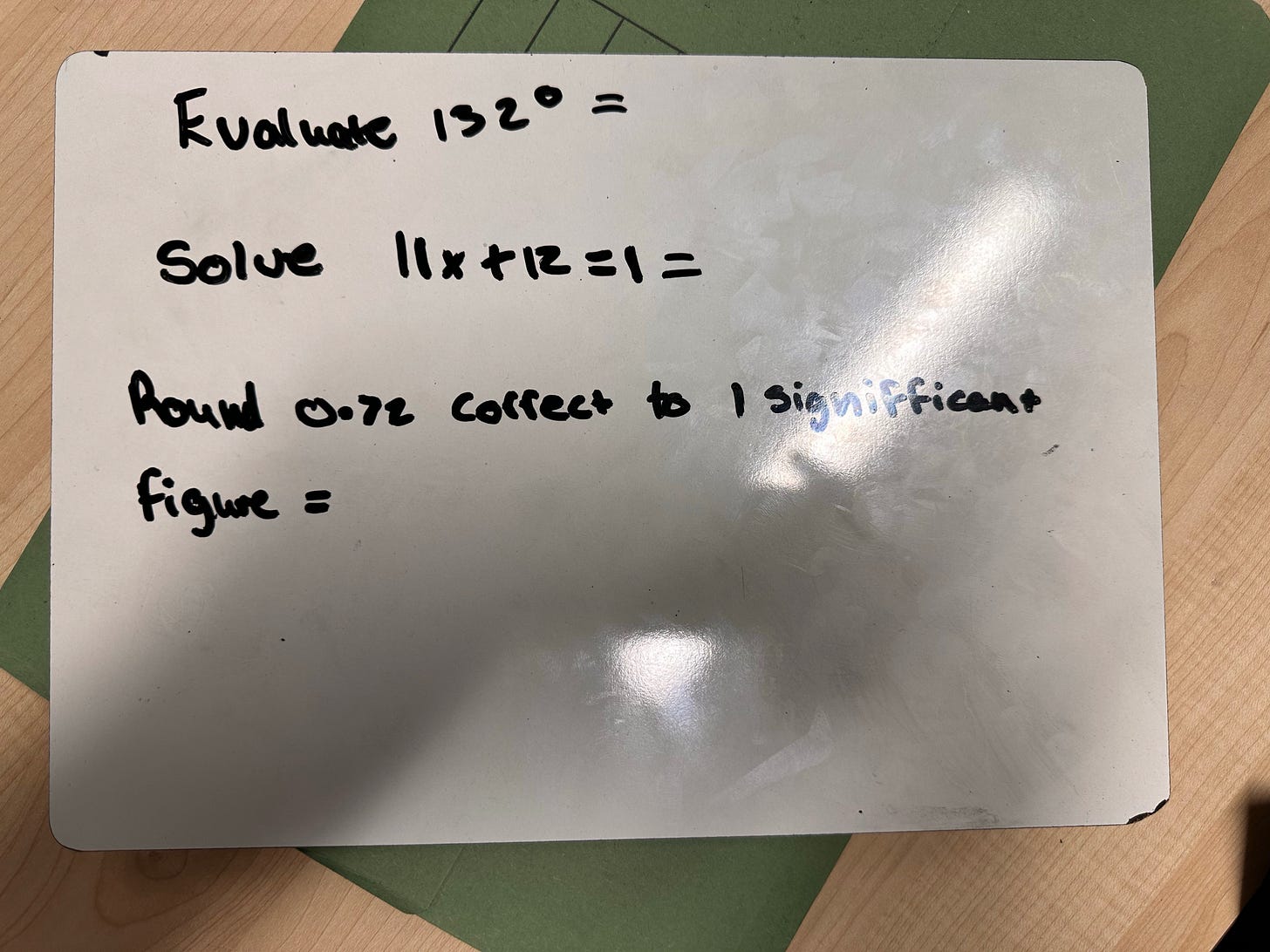

Example

Because you have asked the students to show you three answers simultaneously on their mini-whiteboards, you will miss some wrong answers.

5. Critical evidence

I then spend the next few minutes gathering evidence to support or refute my hypothesis. This evidence must be clear and objective. Examples of good critical evidence include:

Photos

Video

Audio recording

Timings

Data - eg the number of students who got a question wrong

Direct quotes from students or teachers

I hope my evidence-gathering leads me to the conclusion that my hypothesis is wrong, because that means that students are learning more than I feared. If my hypothesis is wrong then - despite my belief that the teacher could do something better - I must ditch it and form a new hypothesis.

Example

Quote from teacher referring to the answer to Q1: Everyone I saw remembered that anything to the power of 0 is 1

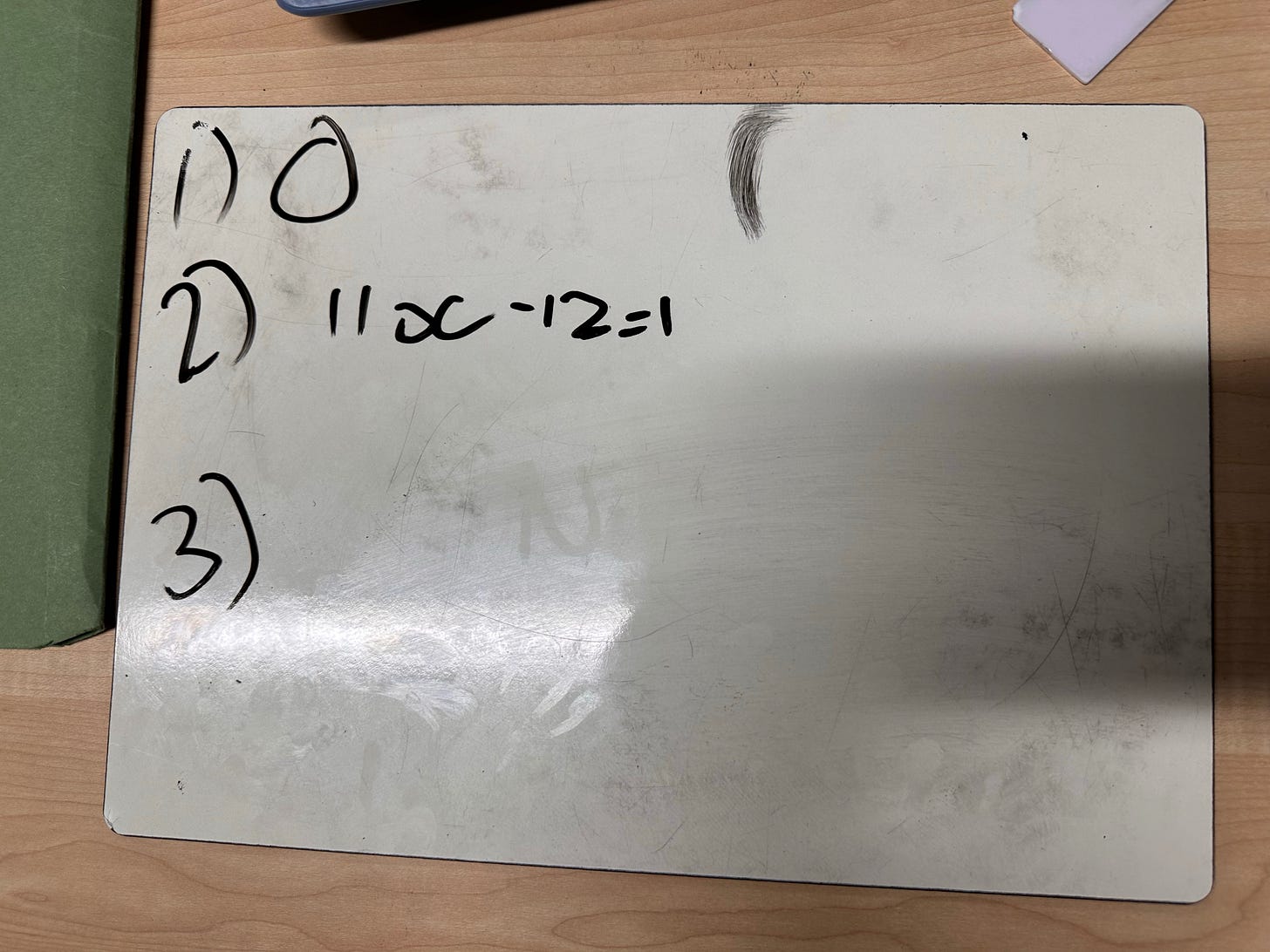

Photos of 5 students’ mini-whiteboards from the back row indicating that several students have got this question wrong or left it out:

6. Diagnostic questions

In the coaching session, following the prompting and discussion of specific praise, I steer the conversation to the lesson phase where I have formed my hypothesis. Another recent change here is that instead of simply presenting my hypothesis, I want to get a sense of the strength of the teacher’s mental model. This will inform me how directive I need to be with the coaching.

So, I will draw their attention to the relevant phase of the lesson and ask them to describe what happened. A photo is really helpful here as it provides the frame of reference and catalyst for recall.

If teachers immediately diagnose the problem, we can jump straight into working on a solution together. If they simply describe the events, I will narrow the focus of my diagnostic question. If this still does not prompt the teacher to realise the issue, I will tell them, using the critical evidence to support my case.

The importance of the critical evidence following the diagnostic question cannot be overstated. Without it, the teacher can, quite rightly, say: well, I don’t agree. And where do you go from there? With some clear, objective critical evidence, presented sensitively, however, most teachers jump on board and are ready to embrace making a change to their practice. This is the most critical and potentially perilous part of the coaching process. If the teacher is not on board, we might as well wrap things up there.

Example

I asked the teacher:

Talk me through how you collected your students’ responses to the Do Now.

His response was to talk me through the mechanics - he used the mini-whiteboards - but then he started describing some element of the third question that was not relevant to what I wanted to talk about.

So, I changed tact and asked a more specific diagnostic question:

How many students got Question 1 wrong?

The teacher thought for a moment and said: at most 3.

I was really careful about how to handle the next bit. The teacher was mistaken, and I had the evidence to prove it. But this is not a gotcha moment where I reveal how smart I am and how foolish the teacher is. I said I thought it might be a bit more than that, and so I tested it by taking some photos of the boards of the students on the back row.

The moment he saw the five photos, he was with me.

I was tempted to dive in and tell him why I thought this had happened, but I wanted to give him the opportunity. Straight away, he had it. There is too much data on the boards!

And then we were off!

7. Suggested actions

With the teacher on board, the coaching session now moves to making improvements. Some important points here:

The suggested action can come from the teacher, or the coach. After presenting the critical evidence and establishing that the teacher is aware of the issue, it is always worth asking: “What do you think we can do about it?”. If they have a strong suggestion, then fantastic as they are likely to buy into it more. If they are unaware, this tells you something valuable about their mental model, and determines how directive you need to be.

The suggested action must be specific and actionable. Just as you don’t want something vague like ask better questions, you also don’t want some mega-complex twelve-step process that will be cognitively overwhelming for the teacher to follow in the heat of a lesson. The key here is a specific step that the teacher can implement in the very next lesson.

There is no point in improving the lesson we just discussed. That lesson has gone, and the teacher might not teach the topic for another year. Far better is to plan improvements for an upcoming lesson.

Plan the step together. Co-script precisely what the teacher will say and do. This helps with buy-in, improves the chances of success, and also reduces the stakes for the teacher due to the shared responsibility. I often say: If this doesn’t work, blame me!

The impact of the suggested action phase lives and dies on whether you rehearse. Not rehearsing is like presenting your students with an explanation and then saying “Does that make sense?” without checking their understanding with a follow-up question. Rehearsal allows you, as a coach, to see if the teacher has understood what has been discussed. It also allows the teacher to try out the idea in a low-stakes environment with the opportunity for immediate feedback, as opposed to in the carnage of a lesson under the gaze of 30 pairs of eyes. I have written more about the importance of rehearsal, along with some tips and strategies, here.

Example

The solution we came up with was that students would do their working on their mini-whiteboards as usual, but when it came to going through the answers they would copy their just final answer for Question 1 from one side of the board and write it nice and big on the other. This will reduce the amount of data the teacher needs to process to just one per board. Students would then repeat this for Questions 2 and 3.

Together we wrote a series of instructions the teacher would give his students when it was time to go through the answers to the next Do Now:

The teacher then rehearsed giving these instructions and checking I was listening. The first time he forgot the third one, so decided to have the piece of paper with him to act as a cue - something he would also do in the lesson.

Then we rehearsed instructing students (ie me) to copy their final answer to the other side of their board, hover the board face down, and only show on 3, 2, 1. At first, I followed his instructions. But as he got more confident, I started not to follow them to the letter so he could rehearse how to deal with that in the classroom.

This rehearsal would have felt weird if I had made it weird (as I did many times before). But now I am careful to explain the purpose of rehearsal in advance, and also jump in and do it myself if the teacher is initially reluctant.

Conclusion

And that is that.

I am by no means an expert at observing and coaching, but this template has undoubtedly helped me to get better. It provides a clear structure that I follow, with each component having a clear purpose. I hope it will prove helpful when thinking about your observing and coaching, whether you are a coach or a coachee.

And one final thanks to Adam Boxer, Ollie Lovell, and Josh Goodrich who have inspired me to try to get better at this.

What do you think of this process for observing lessons and delivering coaching?

What do you like, and what have I missed?

Let me know in the comments below!

🏃🏻♂️ Before you go, have you…🏃🏻♂️

… entered our Eedi competition to win £200?

… read my latest Tips for Teachers newsletter about using the 4-2 approach for independent work?

… listened to my most recent podcast with Jo Morgan about improving GCSE results?

… considered booking some CPD, coaching, or maths departmental support?

… read my Tips for Teachers book?

Thanks so much for reading and have a great week!

Craig

This is such a clear and consice coaching template. I'm an educational psychologist and will definitely give this model a try in my own coaching and observations. Thank you! 👌

Some great ideas, but I can’t find a link to the actual template