Why we sometimes need to chain atoms together

More musings on the process of Atomisation

Places limited! Middle school teacher? Based in the US? Join Eedi's fully-funded math pilot to bring AI-powered tools, live tutoring, and professional learning to your Grade 6 math team. Know a school that might be interested? Read more and apply here!

Listeners to my podcast will know all about my current obsession with Atomisation. I define Atomisation as breaking routines down into their smallest constituent parts (atoms) that can be assessed or taught separately from the routine itself

For a deep dive into the wonderful world of Atomisation, check out my 3 hour conversation with Atomisation guru, Kris Boulton.

Recently, I saw an example of Atomisation not quite working, and I thought it was worth further exploration.

The lesson

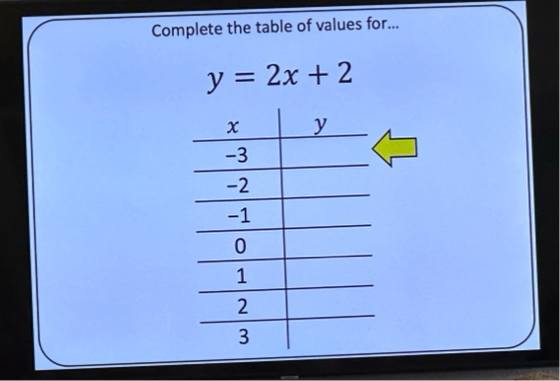

The objective of the lesson was for students to be able to plot straight-line graphs from an equation by filling in a table of values like this one:

The atoms

The teacher had identified that his students needed to be secure with the following Atoms to complete this process successfully:

Reading algebraic expressions

Substituting into formulae

Multiplying with negative numbers

Adding and subtracting with negative numbers

Plotting coordinates on a set of axes

What happened

The teacher assessed each of the atoms with well-chosen questions, and students were able to answer them successfully. So, he moved on to the new routine – filling in a table of values – which used each of these atoms.

He asked his students to think of the value of y when x equals -3.

And his students couldn’t do it.

Suddenly, 2 x (-3) = 6, or (-6) + 2 = -8, despite no students making these mistakes some 30 seconds before.

Why had this happened?

In the coaching session, we discussed why. We hypothesised that the jump from answering questions on individual atoms to carrying out a process involving these atoms combined (interpreting algebraic expressions, substituting, multiplying negative numbers, and adding negative numbers) was too much for these students.

What we should have done – and I take full responsibility here, as I had delivered CPD on atomisation the last time I visited the school – was to chain some of these atoms together before tackling the process.

So, following on from questions like 3 x (-5) and (-4) + 3, we should have included some questions that combined these two atoms and these two atoms alone, such as 2 x (-3) + 1. Students could then have focused on these two atoms without extra attention needing to be diverted towards thinking about the other atoms, such as interpreting expressions and substitution.

Once the chaining of those two atoms was secure, more atoms could be added to the chain until students completed the whole routine.

What I learned

The whole point of Atomisation is to help students thrive with a multi-step process. But the mistake I made was assuming that the leap from nailing individual atoms to being able to chain every atom together to complete the multi-step process was a small one. If there are several atoms, then a more sensible approach is to teach or assess two or three atoms individually and then chain those together. Once students are secure with that chain, teach or assess more atoms and add those to the chain.

Obvious, maybe. But I certainly missed it!

What do you agree with, and what have I missed?

Let me know in the comments below!

🏃🏻♂️ Before you go, have you…🏃🏻♂️

… checked out our incredible, brand-new, free resources from Eedi?

… read my latest Tips for Teachers newsletter about the self-explanation effect?

… listened to my most recent podcast with Ollie Lovell where we discuss the Do Now?

… considered booking some CPD, coaching, or maths departmental support?

… read my Tips for Teachers book?

Thanks so much for reading and have a great week!

Craig

Agreed, as developing the atom-stringing process is behind the idea of faded worked examples, surely? I'm intrigued by the idea of starting at -3 though: I always start at zero myself, work out the positive substitutions of x first and then do the negative values afterwards. I teach my students to spot the pattern and use it to verify the negative x-subs as that's where mistakes are most likely to occur. Some colleagues have even dispensed with negative values of x altogether, though I'm uncomfortable with that as an end point.

Thank you Craige for highlighting the importance of a thoughtful approach to atomisation, acknowledging the need to balance breaking down complex concepts into manageable parts with allowing students to apply their knowledge independently.

I strongly agree with your insightful observation about the delicate balance in atomisation. Breaking down complex concepts into smaller, more digestible 'atoms' is undoubtedly a powerful pedagogical tool, but it's essential to avoid the pitfall of over-scaffolding.

As you mentioned, gradually increasing the complexity of tasks allows students to develop a deeper understanding and the ability to apply their knowledge to novel problems.

However, I believe there's also value in providing opportunities for students to grapple with challenges and make mistakes. By allowing them to 'fall into the pit,' we can foster resilience, critical thinking, and a growth mindset.

Formative assessment plays a crucial role in this process. By regularly monitoring student progress, we can identify areas of strength and weakness and provide targeted support. This enables us to guide students towards more efficient and effective problem-solving strategies, empowering them to independently chain and bind atoms of knowledge to achieve desired outcomes.

Have a great day.