The power of the Hypothesis Model when coaching

Reflections on two days coaching in a primary school

Last week, I spent two days in a lovely primary school supporting a group of teachers to develop their coaching skills. On Day 1, we worked with four teachers. We watched their lessons and then I led each of the coaching sessions, with the coaches taking notes. On Day 2, we watched the same teachers again, but this time each of the coaches took the lead in a coaching session and I provided feedback. It was a brilliant two days, and as ever I learned far more from the teachers I watched and worked with than they did from me.

At the end of Day 1, one of the coaches noted how she really liked the Hypothesis Model I used based on the work of Adam Boxer. So, I thought I would share how this model played out in the four coaching sessions I led in case it is useful to anyone involved in observing lessons, coaching or mentoring.

An overview of the Hypothesis Model

During the lesson observation:

I spend the first 10 minutes getting a sense of the content and pitch of the lesson. I will often sit down next to a student so I can experience things from their point of view

I make a note of specific things I like in the lesson – good questions, explanations, choice of examples

I then form a hypothesis about something that might improve how much students learn (examples below)

I collect critical evidence to test out this hypothesis. Such evidence may be a statistic, a quote, a picture, or a video (again, examples of each below)

An overview of the coaching session:

The coaching session follows this structure:

I begin by asking the teacher to describe the things they did well in the lesson

I supplement this by sharing the specific praise I noted down

I then present my hypothesis and the critical evidence to support it

If the teacher agrees, we then work together to plan a change, decide when they can put it into practice for the first time, and rehearse what this will look like.

Here are the hypotheses, critical evidence, and suggested actions from the four lessons I observed on Day 1.

Lesson 1:

Hypothesis: Students could easily hide a lack of effort or understanding when the teacher was asking questions

Critical evidence (Statistic): Out of the 18 questions asked to the class during the time we observed, 16 were directed at volunteers and 2 were directed at students chosen by the teacher. None required all the class to answer.

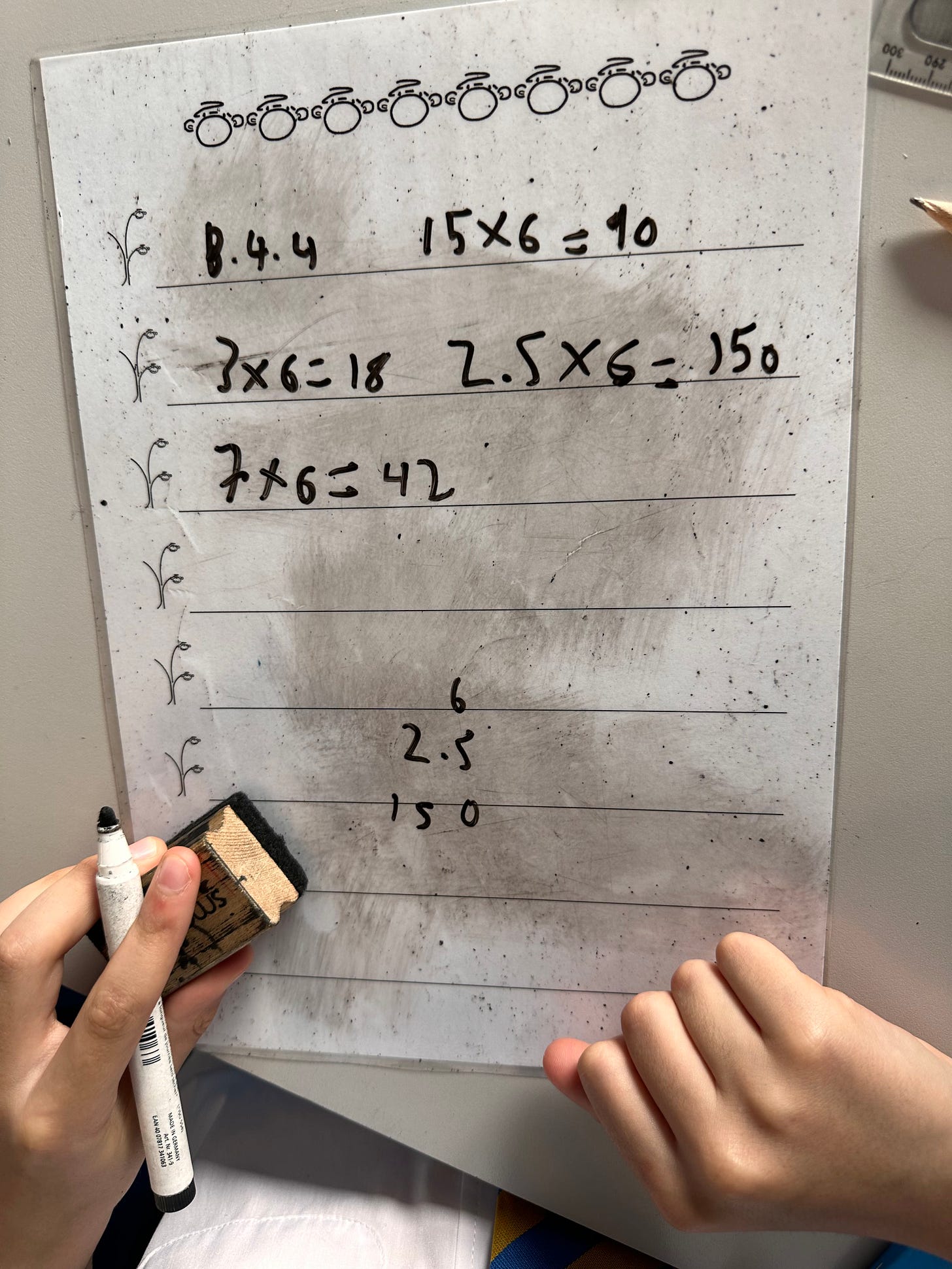

Suggested action: Reduce the frequency of questions where students volunteer, and replace them with Cold Call, Call and Respond and responses via mini-whiteboards

Lesson 2:

Hypothesis: Students were not able to explain the reasons for their answers

Critical evidence (Quote):

Teacher: How many metres in 4.25km?

Volunteer: 4250

Teacher: And how did you get that answer?

Volunteer: I don't know

Teacher: Anybody else?

Volunteer: You do something with the point

Suggested action: Use Supercharged Think, Pair, Share (see this post for full details). The teacher asks a question, and students think and respond independently on mini-whiteboards, showing their response to the teacher when asked. Each pair of students then puts their mini-whiteboards between them to compare answers: If they are different, who is right? If they are the same, what is the best explanation they can come up with that would help someone who does not understand? This provides a key opportunity for students to rehearse their reasons. Then the teacher can call upon students to share their reasoning with the rest of the class.

Lesson 3:

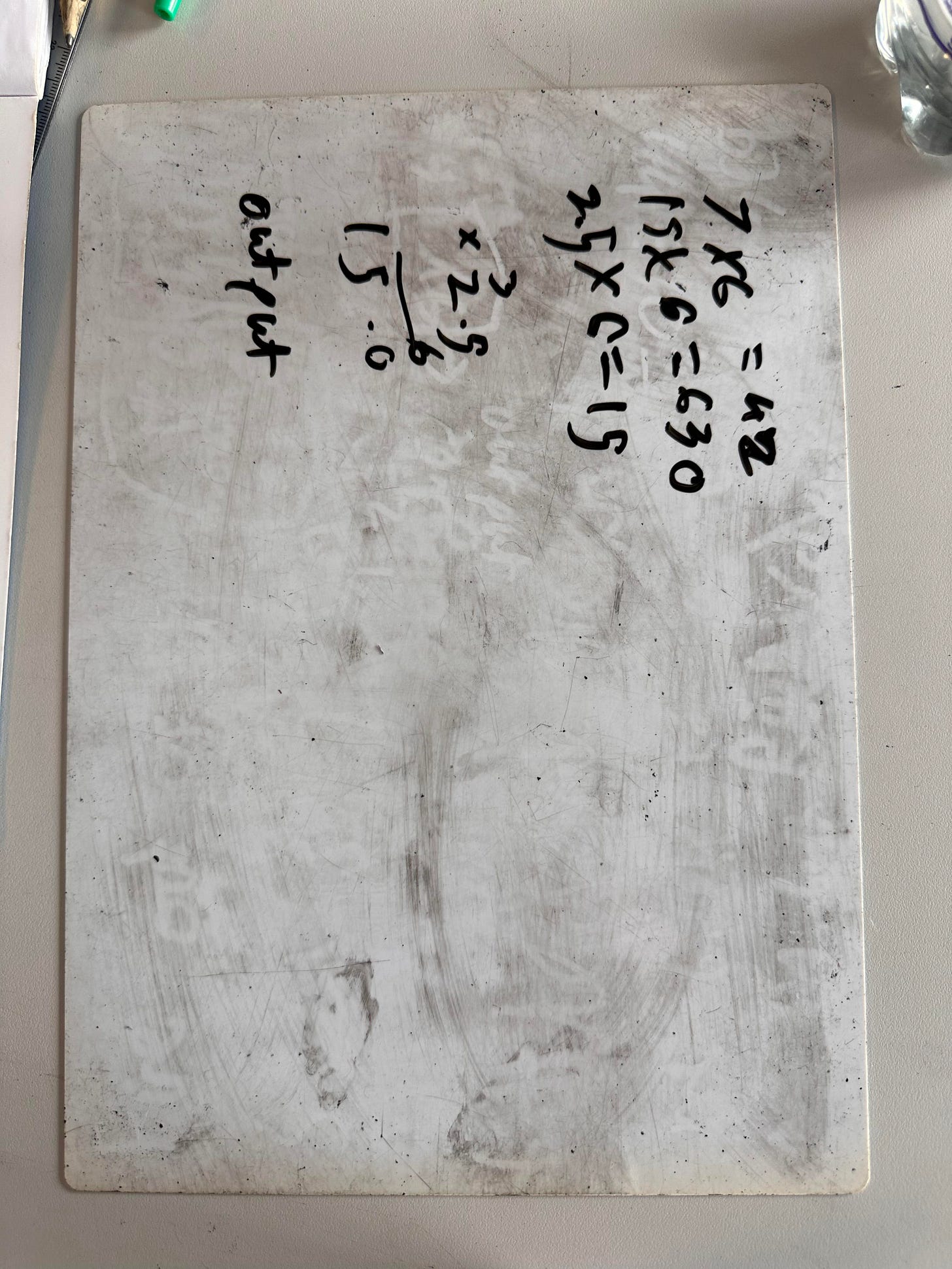

Hypothesis: Students had been asked to answer four questions on their mini-whiteboards. But because they had been given no direction as to how to set their boards out, it was difficult for the teacher to check for understanding when circulating, and virtually impossible to do so if students held their boards up.

Critical evidence (Photo):

Can you see the two incorrect answers? These were not picked up on by the teacher.

Suggested action: Ask students to split their boards into quadrants and do working out for each question in a defined space. This makes checking for understanding during circulation much easier. Then, when it is time to go through the answers, ask students to copy the final answer for Question 1 on the other side of their board nice and big, ready to hold up. Once the teacher has responded accordingly, students can rub out the answer and copy the final answer to Question 2, and so on.

Lesson 4:

Hypothesis: Many students were not listening to the teacher or each other

Critical evidence (Video):

Teacher: How many metres in a kilometre?

Four hands went up.

Volunteer: 1000

Teacher: Correct, there are 1000 metres in a kilometre. Now, let me check if you are listening. How many metres in a kilometre?

One-third of the hands in the class went up. The teacher chose one of those students to answer

Later in the lesson, many students got stuck when asked to convert 6000m into kilometres

Suggested action: Ask more checking for listening questions, and insist on 100% participation. The two strategies we planned and rehearsed were: pushing for all hands to be up when asking a checking for listening question (and asking any student who does not raise their hand why they haven't); and using Call and Respond such as: "Everyone, repeat after me: 1000m is equivalent to 1km... (class repeats)... 1000m is equivalent to... (class responds)... 1km is equivalent to... (class responds)"

Reflections

Some final thoughts:

The hypothesis gives a clear focus to the lesson observation. It allows you as an observer to strip out all the background noise and zone in on a single aspect of teaching and learning, considering how it could be improved.

The critical evidence collected is often the key to the success of a coaching session. It is objective, tangible, and unavoidable. When presented in the right way, it is the point in the coaching session where the teacher goes "oh yeah, I see that", and then the door is open for change to occur

This is the first time I have experimented with video to support my coaching. Obviously, no-one likes being filmed. But I know of no better way to reflect on your own practice than to watch it play out in full, free from all the things that consume your attention in the midst of teaching a lesson. It takes the critical evidence to the next level. For the geeks out there, the set-up I use is an iPhone on a tripod with a wireless mic clipped onto the teacher.

It is important to choose a single, easily implementable strategy, especially in the first coaching session. We want to give success the best chance of occurring, so we can build upon it going forward. Coaching sessions where the teacher leave with 3 or more things to implement simply do not work.

The improvements each of the teachers made on Day 2 were incredible, and the effect on student engagement and understanding was immediate.

Coaching like this will only ever work if it is part of a continual programme. The challenge I always present to the member of the leadership team who hires me is to consider how they will keep this going after I leave.

I am booked up for coaching, departmental support and CPD until November, but I do have capacity after then. So, if you are interested in finding out more, check out this page.

Having spent two days in a primary school, I am perfectly happy teaching secondary school students, thank you very much. Hats off to our primary colleagues!

Three final things from Craig

Have you listened to my recent conversation with Ollie Lovell, where we discuss connections, worked examples and iPads?

You can see the back catalogue of all my Eedi newsletters and Tips for Teachers newsletters here

Have you checked out my Tips for Teachers book, with over 400 ideas to try out the very next time you step into a classroom?

If you found this newsletter useful, subscribe (for free!) so you never miss an edition, share it with one of your colleagues, or let me know your thoughts by leaving a comment.

Thanks for reading and have a great week!

Absolutely loved this clear explanation of the model in practice, and the vivid (and very familiar) examples. I sometimes have had much of this in my head while coaching, but there is great value in making it more explicit — both to have clear language to support our own thinking and decision-making as coaches, and to be able to share this better with the teacher (and anyone else involved).

I think you discussed this with Adam, but what if a teacher does not agree with your hypothesis & critical evidence? What does the story tree look like after that? During Ollie Lovell & Goodrich's coaching session, Ollie disagreed with some of Goodrich's initial pitches, but I don't remember how Goodrich reacted. I think he had another hypothesis that he presented to Ollie.