Poor proxies for understanding

How many of these do you recognise?

This newsletter is made possible because of Eedi. Check out our brand-new set of diagnostic quizzes, videos, and practice questions for every single maths topic, ready to use in the classroom, and all for free, here.

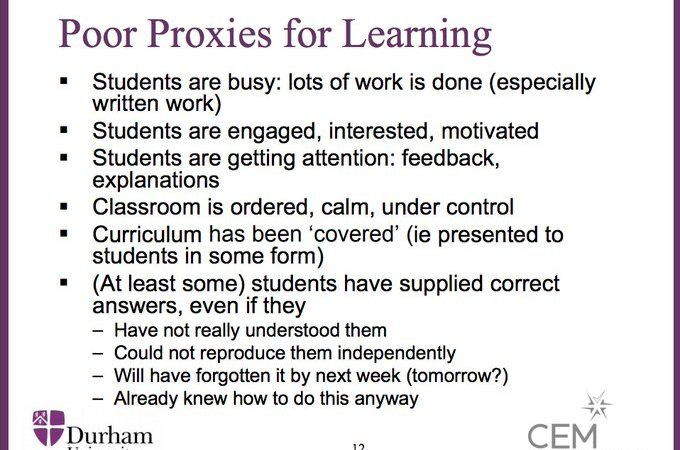

One of the most influential things I read when researching my first book, How I wish I’d taught maths, was Professor Rob Coe’s poor proxies for learning. In case you are not familiar with them, here they are:

The point is that each of the things on Rob’s list is easily observable and could indicate that learning is taking place, but there is no guarantee. And if, as teachers, we do not seek more reliable evidence of learning above and beyond these proxies, then we are taking a big risk.

In this post, I’d like to propose my own list that I am calling Poor Proxies for Understanding. These observations are based on the hundreds of lessons I have seen recently, and I have been seduced by every single one in my own teaching. As with the list above, each of these things could indicate that students understand, but the subsequent performance of students later in the lesson suggests understanding is not where the teacher hoped it would be.

Here is my list:

What are your initial impressions?

Which do you immediately agree with, and which do you question?

Let’s look at each in turn.

The response of one student

This is a classic that dogged my teaching for years. Sure, the response of one student may tell you a lot about the understanding of that student, but what about the rest of the class? Is their response likely to be representative? If the student in question is a confident, high-attaining student who has volunteered an answer, then the chance is likely to be low. But even if the teacher has chosen a student to answer via Cold Call, it feels risky to hope that their response is representative of the response of all their classmates. And will any student who thinks something different really tell you?

Students nodding

Students learn pretty quickly that if they look like they understand something, the chance of them being asked to prove their understanding is low, especially if their mate is looking out of the window or filing a rubber with their ruler. A nod is a great way to give the impression you understand. Perhaps some readers will admit, like me, that you have nodded your way through a meeting or two whilst not having a clue what is going on.

Students copying things down

The teacher gives an explanation, the students look on confused, and then that magic instruction is given: copy this down into your books. In my posts, The Myth of Copying Things Down and Correcting in green pen does not work, I argue that a neat exercise book full of notes and corrections is a poor proxy for learning. Copying masks a lack of understanding, and the time it takes means actual checks for understanding get squeezed out. And yet, copying things down has become so ingrained in a lesson’s synopsis that it is done without question or complaint.

Students not asking questions

“Has anybody got any question?” said me, after many a muddled explanation. The issue is not with the question itself, but the assumption that the silence that inevitably follows is a good proxy for understanding. There are a whole host of reasons why students may not ask a question - fear of being wrong, fear of letting you down, shyness, apathy, they understand so little that they cannot even form a question, and so on. And yet time and again this question serves as a teacher’s sole check for understanding.

Students telling you they understand

Surely if students tell you they understand something it means that they do? Well, not necessarily. My Diagnostic Questions co-founder, Simon, and I tested this a few years ago. We asked 10,000 students a bunch of multiple-choice maths questions and asked them to rate how confident they felt in each of their answers. Hence, for each student, we had a measure of actual understanding (the proportion of questions they got correct) and a measure of their perception of understanding (their average confidence rating). The results looked like this:

Sure, there is a positive correlation. But look at the spread. The key point is that for any given level of confidence, we cannot be sure of actual understanding. So, any question that ascertains students’ perception of their understanding - Does that make sense? Is everybody happy? etc - is likely to be a poor proxy for actual understanding.

As an aside, the graph above suggests something else: students telling you they don’t understand something may also not be a true reflection of their actual understanding. It is worth experimenting with not giving students a chance to tell you they are confused and instead jumping straight into an opportunity for them to demonstrate what they can do, and they might just surprise themselves.

A better proxy for understanding?

The best proxy for student understanding is their response to a well-chosen question that assesses the concept you want to check. The question could be multiple-choice or open-response. Ideally, it should elicit mass participation - ABCD cards or using mini-whiteboards - to avoid the first poor proxy. You will then have a much better sense of what your students do and don’t know so you can respond accordingly. This doesn’t have to be for every single question you ask, but at critical points in the lesson, striving to see the responses of every student in the class is a worthy aspiration.

And if students’ responses reveal that understanding is not secure, and we subsequently intervene with an explanation or correction, then we need to recheck for understanding in the same way, lest we find ourselves falling for one or more of these proxies again.

This might well be the most obvious thing you have ever read. But I have been seduced by enough of those poor proxies over the years, and seen enough teachers seduced by them over the last few weeks, to deem it worthy of a post.

Which of those proxies have you fallen for?

What do you agree with, and what have I got wrong?

Let me know in the comments below!

🏃🏻♂️ Before you go, have you…🏃🏻♂️

… checked out our incredible, brand-new, free resources from Eedi?

… read my latest Tips for Teachers newsletter about asking students not to clean their mini-whiteboards?

… listened to my most recent podcast about rehearsal, CPD and asking who got 8/10?

… considered booking some CPD, coaching, or maths departmental support?

… read my Tips for Teachers book?

Thanks so much for reading and have a great week!

Craig